In our first installment of this series, we explored what the gender data gap is and the negative impact that it has on our collective ability to truly achieve the SDGs for all people. In this post, we examine how gender and natural resource management intersect.

Why making women visible in natural resource management matters on multiple levels

As noted in the first post of our gender data gap series, SDG 14, which aims “to conserve and sustainably use the oceans, seas, and marine resources for sustainable development” is one of the six SDGs lacking any gender-specific indicators. UN Women’s Progress on the SDGs: gender snapshot 2022 explains that women are disproportionately affected by the destruction of Earth’s natural resources, including its forests and oceans, due to their “limited access to and control of land and environmental goods, exclusion from decision-making, and the higher likelihood of living in poverty.” The reliance of women on natural resources and their substantial economic contributions to resource-centered livelihoods begs for formal recognition from governments worldwide. “Women and their communities must be engaged in solutions that affect their environment, their livelihoods, and their way of life,” the brief aptly states. Therefore, harnessing the power of gender-specific data better enables agents of change to lead the charge for female inclusion when it comes to natural resource management decision-making and the formal recognition of their livelihoods.

Such is the case in Indonesia, an archipelagic nation of 17,000 islands where fishing is the way of life for six million people. “Although they are present in every fish market throughout the country, no official or formal record exists for the total number of women vendors, nor for the volumes of fish that they sell,” states a Medium article on the topic. By default, women are legally registered as housewives on their ID cards, rather than as fishers, despite the major contributions they make to local fishing economies. This misrepresentation of their profession causes them to miss out on equal access to the different types of government support afforded to their male fisher counterparts.

Indonesian women’s solidarity organization, Solidaritas Perempuan, argues that the form of marine spatial planning developed and implemented in the country has a patriarchal logic. “RZWP3K (the marine spatial plan) is allocating space to different sectors. Who is the most important in this? Some people will lose. In Indonesia, there are patriarchal priorities – big projects. But for us creating jobs for women in fishing communities should be a priority, but they are not seen. Women are invisibilized and therefore will lose.” Solidaritas Perempuan is collecting data on the gendered impacts of these types of big infrastructure projects so that these kinds of natural resource injustices aren’t perpetuated. They also use education and action research to mobilize women so that they can voice resistance in the face of future projects designed with a gender bias.

Excluding women from resource management efforts doesn’t simply harm women, a considerably heinous act in itself. It also further harms the environment, as a growing body of evidence shows that women’s participation and leadership are associated with better resource governance, conservation outcomes, and disaster readiness according to a 2022 World Bank article.

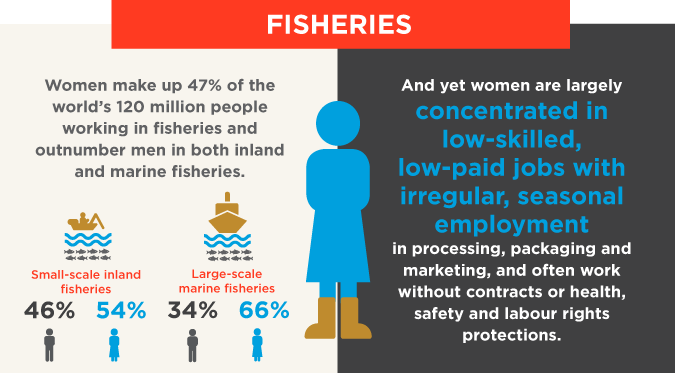

Gender-specific data collection related to fisheries is lacking worldwide, based on patriarchal notions of what comprises fishing activity. “Fishing has long been considered a male domain, i.e., it is often assumed for social, cultural, or religious reasons that women do not participate in fishing activities,” states the 2020 PLoS ONE article ‘Valuing invisible catches: Estimating the global contribution by women to small-scale marine capture fisheries production.’ We know, however, that women make up nearly half of seafood workers worldwide.

Image Credit: UN Women Americas and the Caribbean, “In focus: Women and the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs): SDG 14: Life below water”

The article goes on to discuss that because fisheries’ data collection and management efforts have historically focused on large-scale commercial fisheries (a notion strikingly similar to the ‘big’ infrastructure projects in Indonesia mentioned above), the differing harvest methods, species of interest, and motivation behind women’s participation in capture fisheries largely go unmeasured. They add that women regularly participate in the nearshore collection of small fish and invertebrates like shellfish. They then either sell their small-scale harvest in the informal economy or supplement their family’s home consumption. Missing these key data points on the movement of natural resources and their potential economic impact makes the overarching goal of SDG14 to sustainably utilize marine resources for development elusive and unattainable. The research behind Valuing invisible catches was the first attempt to assemble quantitative estimates of catch by women and their associated landed value on a global scale. The authors estimated this figure to be USD 5.6 billion (+/- 1.5 billion.) Regional differences notwithstanding, this figure provides justification that sex-disaggregated fisheries data is essential for governments to collect and for policymakers to utilize in broader fisheries planning and management efforts. Furthermore, if more comprehensive data was collected on the fisheries industry as a whole, looking beyond harvesting to also include processing, the percentage of women’s involvement in the sector increases substantially, as women are much more often seen in these roles.

Overall, women’s contributions to fisheries play a positive role across multiple Global Goals, including food security, livelihoods, sustainable resource management, responsible consumption, and economic growth. Data gaps on how women participate in, manage, and benefit from marine resources could be closed even faster through the advancement of digital services, which we will explore more in our final upcoming installation.

Published Aug 25, 2023